Notable Tropical Storms

Hurricanes: Tropical Storm Science 🌀 Hazards 🌀 Notable Storms 🌀 Climate Change 🌀 Hurricanes Database 🌀 NC Landfalls

No matter their timing, track, or even their intensity when they reach us, tropical storms of all sorts can have major impacts across North Carolina. We’ve seen this especially in recent years, with every corner of the state being affected by tropical systems.

Historical Hurricanes

Among bygone storms, several big names – and prior to the advent of storm naming in the 1950s, a number of other notable events – stand out. In the late 19th century, a pair of destructive Category-3 hurricanes lashed our coastline, even sending Governor Thomas Jarvis seeking shelter from a storm in Beaufort in 1879.

North Carolina’s strongest landfalling hurricane, Hazel in 1954, leveled parts of our southern coastline with Category-4 winds and an 18-foot storm surge. Inland, Hazel also brought hurricane-force gusts and widespread wind damage across the Piedmont. In similar fashion, Hugo in 1989 was a major wind-maker for the western Piedmont.

And in the Mountains, a small but significant set of impactful remnant storms includes the events of July 1916 and August 1940. Each caused deadly flooding along our western rivers and streams, with the 1916 event inundating the southern Mountains, including Asheville, while a pair of 1940 storms devastated northern areas such as Boone.

The Atlantic Heats Up

The tropical Atlantic Ocean entered a period of elevated activity by the mid-1990s, and multiple storms affected North Carolina, beginning with the back-to-back hits from Bertha and Fran in 1996. Each storm pounded our southern coastline with Fran – our most recent landfalling major hurricane – also whipping up winds and toppling trees and power lines on its inland track that came directly through Raleigh.

Another pair of storms targeted eastern North Carolina in September 1999. The slow, meandering Hurricane Dennis offshore, followed less than two weeks later by a direct hit from Hurricane Floyd, combined to create unprecedented freshwater flooding as the Cape Fear, Neuse, and Tar rivers each reached new record crests and spilled their banks into coastal towns and farms.

The early 2000s saw a series of storms affecting either end of the state. Hurricane Isabel in 2003 had landscape-altering impacts along the Outer Banks, while three storms in one month – Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne – led to flooding and landslides in the Mountains in September 2004.

Modern Flooding Storms

Over the past two decades, North Carolina has seen multiple heavy rain and flood events from tropical storms, their remnants, and even some close atmospheric cousins, such as the upper-level system fed by moisture from Hurricane Joaquin in 2015 and the offshore Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight in 2024 that both produced extreme rainfall totals at our southern coastline.

In eastern North Carolina, the record river levels and damage totals from Floyd were topped by Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018. Each brought extreme rainfall totals exceeding 18 inches, and in Florence’s case, of almost 36 inches. Even minor remnant storms such as Tropical Storm Idalia in 2023 produced locally heavy rain and flooding in low-lying areas such as Whiteville.

Western North Carolina has seen its own modern flood events from the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred in 2021, which caused deadly flooding on the Pigeon River, and from Hurricane Helene in 2024, which became the new flood of record across the region, along with North Carolina’s costliest and deadliest hurricane on record.

Even the Piedmont has seen the full range of hurricane impacts in recent years. The remnants of Hurricane Michael brought widespread wind damage in 2018, Helene spawned multiple tornadoes in our northern counties, and localized flooding occurred in the Charlotte area during Tropical Storm Debby in 2024 and in Burlington and Chapel Hill after Tropical Storm Chantal in 2025.

Recent Rainfall Stats

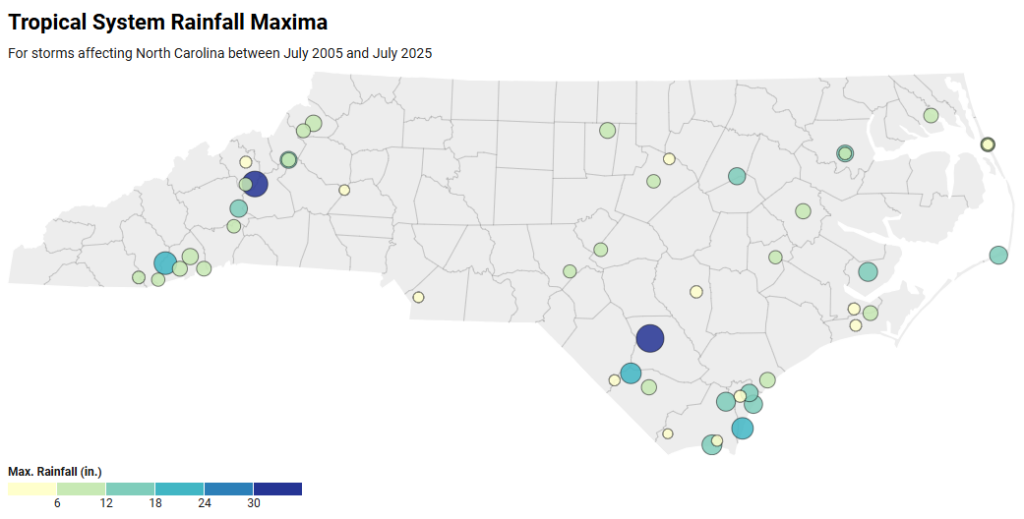

Over the two decades from 2005 to 2025, a total of 50 tropical systems or their remnants affected North Carolina. That’s an average of 2.5 storms per year, while the most active years have seen as many as 8 storms affect our state in 2020.

While only 9 of these storms reached us at hurricane strength, 38 of them – or 76% – still produced at least six inches of rain somewhere in the state. And maximum in-state rainfall totals from these storms occurred in all regions of North Carolina.

The Mountains notably saw extreme amounts of 23.41 inches in Lake Toxaway from Tropical Storm Fred and 31.33 inches in Busick from Hurricane Helene. The Piedmont had up to 10.49 inches during Chantal. And numerous sites across the Coastal Plain have been our wettest spots during tropical events, with more than 12 inches of rainfall.

It’s a lesson that no part of the state is protected from tropical storm impacts, and as our climate changes to make storms even wetter, these heavy rain events are becoming even more pronounced and widespread.